Cold-water immersion therapy (i.e., “Ice Baths”) is fast becoming a popular thing on social media. It’s not uncommon to see someone jump into ice cold water. Researchers have shown ice baths to be beneficial for recovery from training/competition (1). But what are the perceptions from the people on the ground? Do coaches and athletes use them? And if so, how do they apply it?

In 2021, Allan and colleagues (2) sent out surveys to ask athletes/coaches/support staff about the use of cold-water immersion (CWI) for recovery. Specifically, they asked about their current CWI methods, their perceptions around the benefits, and the knowledge around the underlying mechanisms of CWI and recovery. They got 111 responses from athletes, coaches, and support staff (i.e., medical staff, S&C, sport scientists) in both the recreational and high-performance setting.

Key Findings:

- Mostly positive perceptions toward CWI.

- Methods were sometimes inconsistent with recommendations – highlighting the knowledge transfer gap.

- Research should look into possible psychophysiological benefits (i.e., how perceived recovery from CWI may impact physical recovery). (such as?).

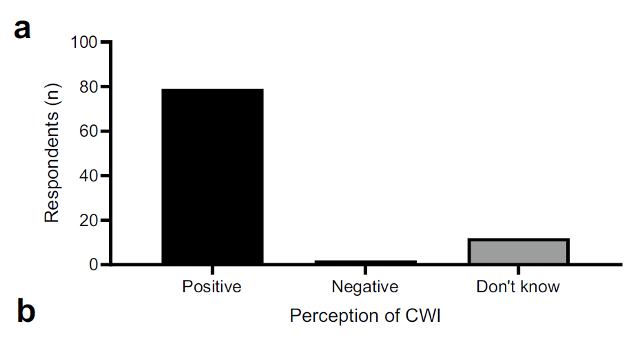

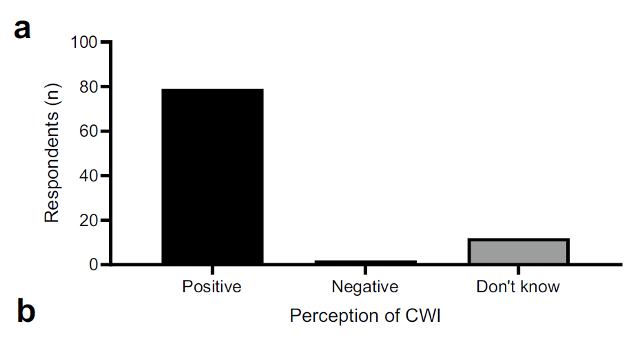

The authors found that 85% of respondents had a positive perception toward CWI (with only 2% having a negative perception). When asked for further details as to “why?” a common answer was that athletes felt “fresher/refreshed” and that it helped recovery following exercise. This finding was mirrored by 86% of respondents prescribing/using CWI as a means of recovery.

Figure 1: Overall perceptions of CWI by athletes/coaches/support staff. Taken from Allan et al., 2021.

Empty space, drag to resize

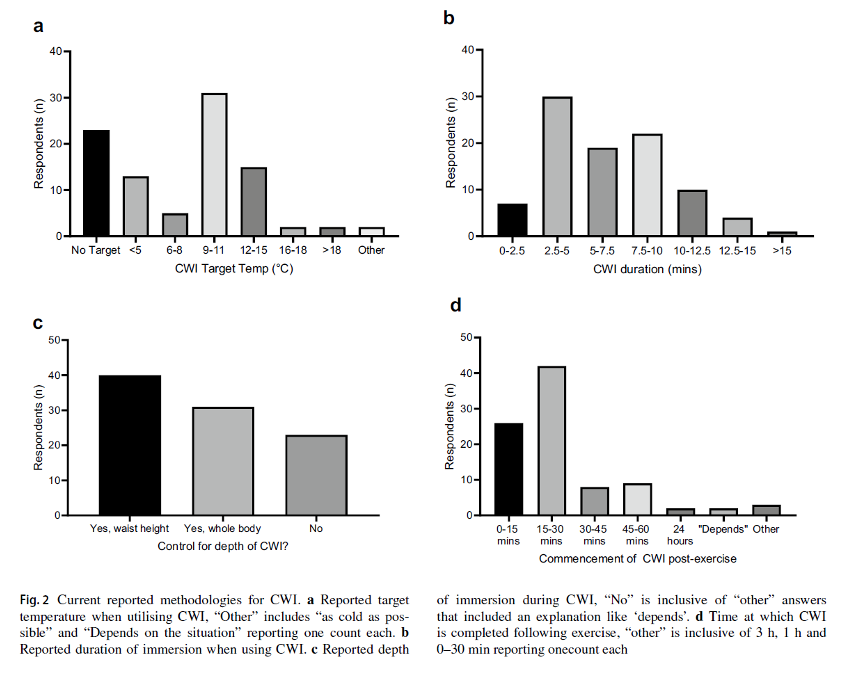

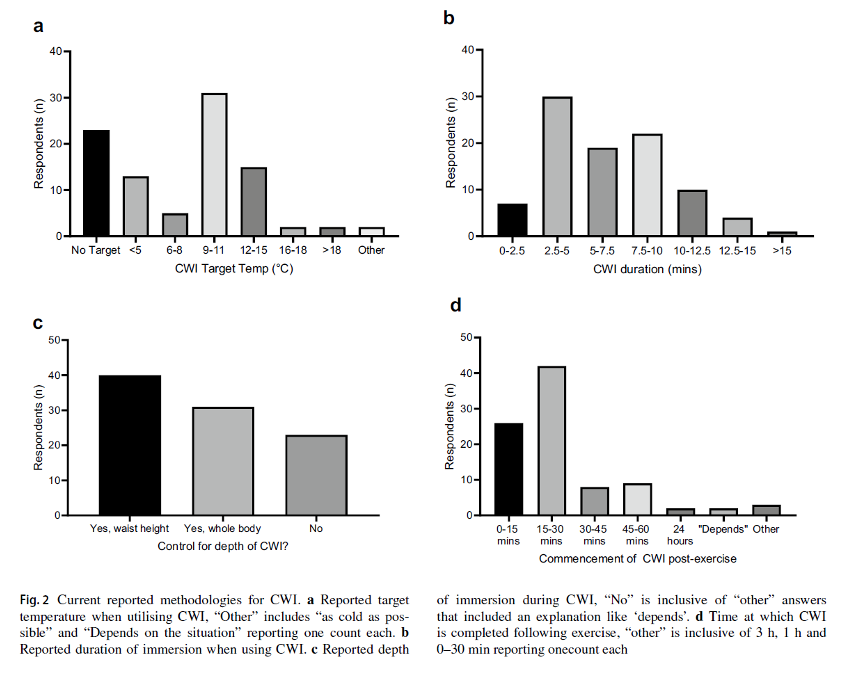

When asked about the protocols used for CWI, majority of respondents reported that they used temperatures of 9-11°C for 2.5 to 10 min in a single immersion within 30 min after exercise. Interestingly, while the temperature falls within the recommended range for optimal benefits (10 to 15°C)3 the duration may be slightly too short (only 14% of respondents used the recommended duration of 10-15min) (3).

Upon further questioning, the authors found that typically the support staff used procotols that more closely matched to the researchers recommendations compared with coaches and athletes. This, to them, highlighted two things:

1) The gap in research translation.

2) The benefits of additional support staff in a multi-disciplinary performance team.

Figure 2: Current methodologies used by coaches/athletes/support staff for CWI. Taken from Allan et al., 2021.

Despite a clear positive perception towards CWI and common usage, there appears to be less clarity around the mechanisms of action. The common benefits believed by respondents were a reduced post-exercise inflammation as well as reduced pain and muscle soreness. While the authors note that reduced pain and muscle soreness following CWI are well established, the effects on post-exercise inflammation may not be. The authors highlight that there is some evidence that shows CWI can reduce markers of post-exercise inflammation, there also remains a large body of evidence to suggest that it may have no effect. Despite the debate around inflammation, the beneficial effects on recovery may still remain.

Interestingly, the authors also noted common themes that arose when they asked athletes about their experiences with CWI. In addition to feeling “fresh/refreshed”, they mentioned feeling a “heightened sense of recovery”, a “feel-good factor”, and a “mind-body connection”. This brought attention to the possible psychophysiological benefits of CWI. The authors demonstrate how believing something improves recovery may actually help you recover. The example they use was a paper by Broach et al. (2014) (4) who compared CWI to a pH neutral soap that they suggested to participants enhanced recovery (but actually didn’t). Interestingly, the soap group (i.e., placebo) showed a similarly enhanced recovery to the CWI group. This demonstrates the power of placebo when it comes to recovery and the authors note that this “psychophysiological” effect that may be associated with CWI is something to be studied further.

Clearly there is a good perception around, and fairly widespread use of CWI for enhancing recovery and performance of athletes. However, sometimes in practice, CWI is not applied as recommended for optimal effectiveness. This highlights the need for improved research translation as well as the appointment of support staff (i.e., medical staff, S+C, sport scientists). Additionally, further research should look into the psychophysiological (i.e., “feel good factor”) effects of CWI.

For more info on cold-water immersion and other recovery strategies for athletes, sign up to

SSISA Research Digest

Empty space, drag to resize

References:

1. Ihsan M, Watson G, Abbiss CR. What are the Physiological Mechanisms for Post-Exercise Cold Water Immersion in the Recovery from Prolonged Endurance and Intermittent Exercise? Vol. 46, Sports Medicine. Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 1095–109.

2. Allan R, Akin B, Sinclair J, Hurst H, Alexander J, Malone JJ, et al. Athlete, coach and practitioner knowledge and perceptions of post-exercise cold-water immersion for recovery: a qualitative and quantitative exploration. Sport Sci Health [Internet]. 2021;18(3):699–713. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-021-00839-3

3. Machado AF, Ferreira PH, Micheletti JK, de Almeida AC, Lemes ÍR, Vanderlei FM, et al. Can Water Temperature and Immersion Time Influence the Effect of Cold Water Immersion on Muscle Soreness? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sport Med. 2016;46(4):503–14.

4. Broatch JR, Petersen A, Bishop DJ. Postexercise cold water immersion benefits are not greater than the placebo effect. Med Sci Sports Exerc [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2024 Jan 26];46(11):2139–47. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/James-Broatch-2/publication/261184764_Postexercise_Cold_Water_Immersion_Benefits_Are_Not_Greater_than_the_Placebo_Effect/links/5d0ff9ae458515c11cf2e117/Postexercise-Cold-Water-Immersion-Benefits-Are-Not-Greater-than-the-Placebo-Effect.pdf