Developing muscular strength and endurance are described as fundamental components within health-related physical fitness. An increase in the number of scientific publications have been seen over the years, ranking resistance training as a top 10 world-wide trend (1).

Studies show that participating in regular resistance training yields positively on body composition (1,2), blood pressure (1,3), bone mineral density (1,4) and insulin sensitivity (1,5). For older adults above the age of 50 years, resistance training has been reported to decrease age-associated loss of muscle mass, which is referred to as sarcopenia (6).

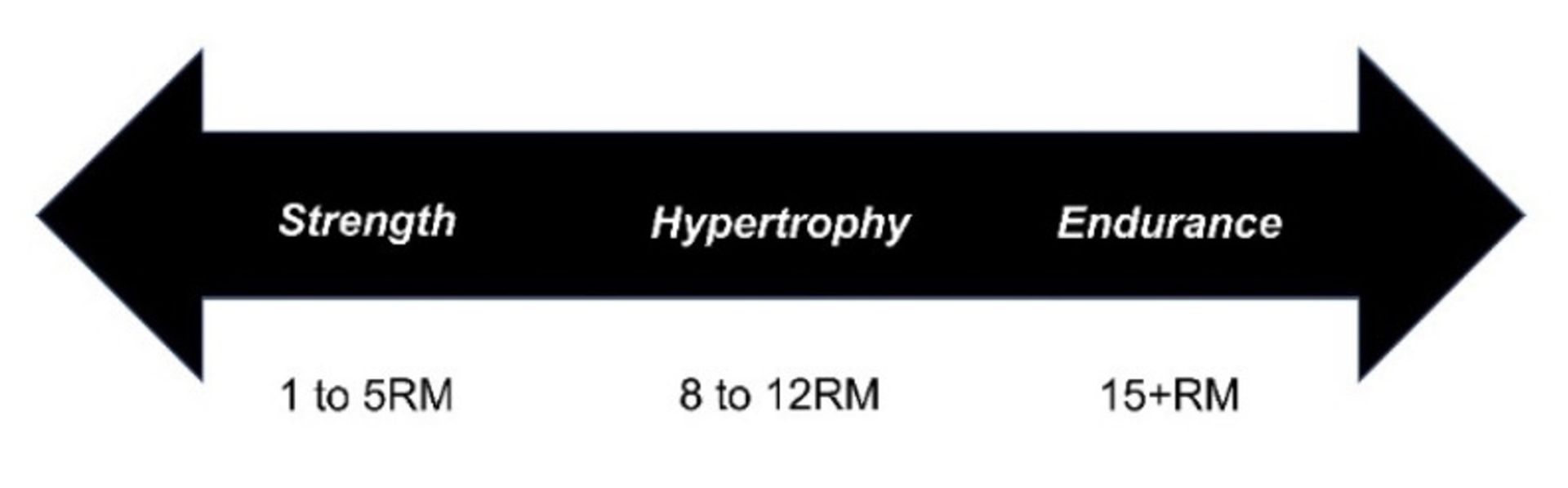

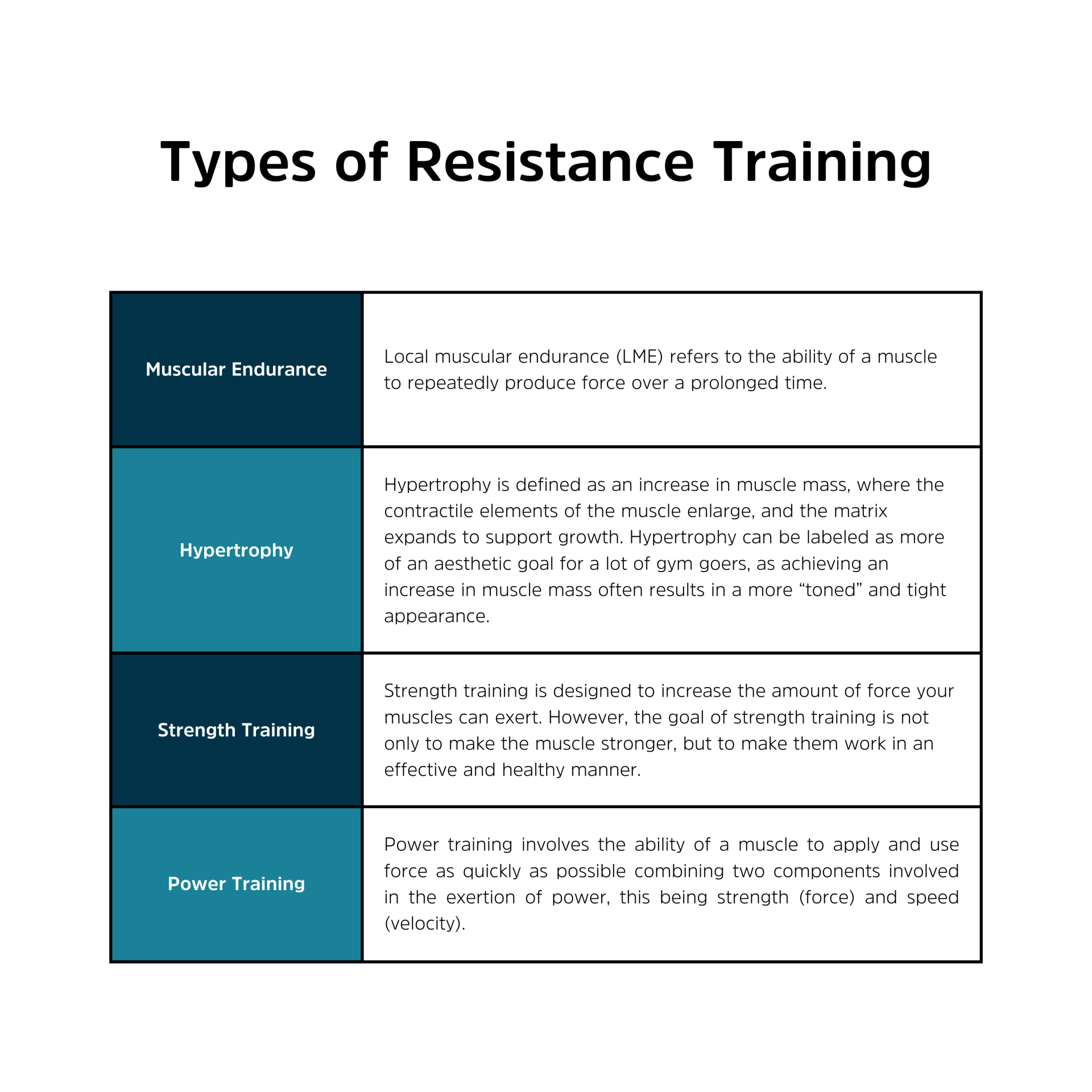

In general, a good resistance/strength training programme should focus on improving health and fitness variables, and should include a variety of different exercises that target different major muscle groups at each training session (7). An increase in lean body mass as a result of resistance training is reported to contribute to basal metabolic rate (BMR), whether maintaining BMR or increasing it. In general, resistance training involves a specialized application of physical exercise and conditioning that includes progression, and a wide range of resistance (also termed load) into different exercise and training modalities that promote the development of muscular fitness (1).

Studies show that participating in regular resistance training yields positively on body composition (1,2), blood pressure (1,3), bone mineral density (1,4) and insulin sensitivity (1,5). For older adults above the age of 50 years, resistance training has been reported to decrease age-associated loss of muscle mass, which is referred to as sarcopenia (6).

In general, a good resistance/strength training programme should focus on improving health and fitness variables, and should include a variety of different exercises that target different major muscle groups at each training session (7). An increase in lean body mass as a result of resistance training is reported to contribute to basal metabolic rate (BMR), whether maintaining BMR or increasing it. In general, resistance training involves a specialized application of physical exercise and conditioning that includes progression, and a wide range of resistance (also termed load) into different exercise and training modalities that promote the development of muscular fitness (1).

Physical function and health-related quality of life can be enhanced by regularly engaging in resistance training by circumventing age-related weight gain, and promoting enjoyment and independence of the individual through doing resistance-type exercises that they like participating in (1).